A little over a year after appearing on Kickstarter, Oculus has turned the far-fetched ‘90s science fiction of virtual reality into a wildly successful prototype device: the Oculus Rift. As of this writing, you can snipe enemies in virtual reality with Team Fortress 2. You can hack imaginary computers and see the world through the eyes of a toddler. You can be an elephant and get your head chopped off by a guillotine. But few people would say anyone has found the holy grail of Rift experiences: something that tears up all our rules about good game-making and reconfigures them for virtual reality.

All jacked in and nothing to play: chasing the perfect VR game

Learning to walk

Back when the Oculus Rift was little more than a prototype and a Kickstarter campaign, it was all but granted that we’d be using it for first-person shooters. Oculus had captured the attention of FPS pioneer John Carmack (who would eventually join the company) and every copy of the development kit was set to come with a Rift-optimized copy of Doom 3. As the first units shipped, though, it became clear that just walking, let alone running and gunning, was one of the hardest things to get right.

For all the Holodeck-style promise of VR, trekking through a virtual world is often an intensely uncomfortable experience. Over the course of playing Rift demos, I’d sometimes look down to find that I was apparently either crawling through the level or sinking halfway through the floor: because of the narrow vertical field of view on monitors, says Oculus founder Palmer Luckey, game cameras tend to be placed low to make other characters look more natural. "If you were rendering yourself at the correct height — if you're 6 feet tall and you're talking to someone 6 feet tall — their head would be in the center of your screen, there'd be a bunch of sky on top of them, and you'd only see their chest," he says. In VR, "either you're too short and you know it, because you feel too close to the ground, or if you push that camera up to a reasonable height, it turns out that a lot of doorways are about to decapitate you. Entire games are built around these things. You can't just go in and say ‘make the door bigger.’"

Trekking through a virtual world is often an intensely uncomfortable experience

Even if the camera was right, any game that let me walk faster than a leisurely stroll was almost unbearable for more than half an hour. In some ways, Half-Life 2 is fantastic on the Rift — the mild vertigo induced by seeing the ground 20 feet below me in VR made its early rooftop chase more fun than most of the firefights. But every time I turned or strafed, I got a little sicker. Three levels in, I had to stop and spend the next 20 minutes recuperating. Part of the problem is that, as Valve has readily admitted, porting games to VR is a messy and frustrating process. "[In] Half-Life 2, the staircases in that game are nauseating. And that's something so simple: I’m just moving up a flight of stairs," says Devin Reimer of indie studio Owlchemy Labs, which ported Dejobaan Games’ skydiving title AaaaaAAaaaAAAaaAAAAaAAAAA!!! for the Awesome to the Rift. "But the way that it's implemented in that game, because it is sort of just virtual reality support patched on top, you end up running into things like that."

The developers I talked to promised I’d develop "VR legs" with time, and though I haven’t tried it, a new version of the headset is supposed to make things much better: its high resolution and reduced latency will get rid of the dizzying motion blur you see when you turn too fast, and Oculus is working on implementing real positional head tracking, which will make your head motions match up to what you see on the screen. For better or worse, though, shooters as we know them — with their nimble, omnidirectional avatars — are probably never going to work on the Rift. "When was the last time you ever moved backwards quickly in real life? It sends your brain almost into a panic mode," says Luckey. "When you're talking about a game like Team Fortress 2 where you're just booking it at 20, 30, 40 miles [per hour] backwards, that's a really disorienting experience and it doesn't feel good in VR at all."

The uncanny VR valley

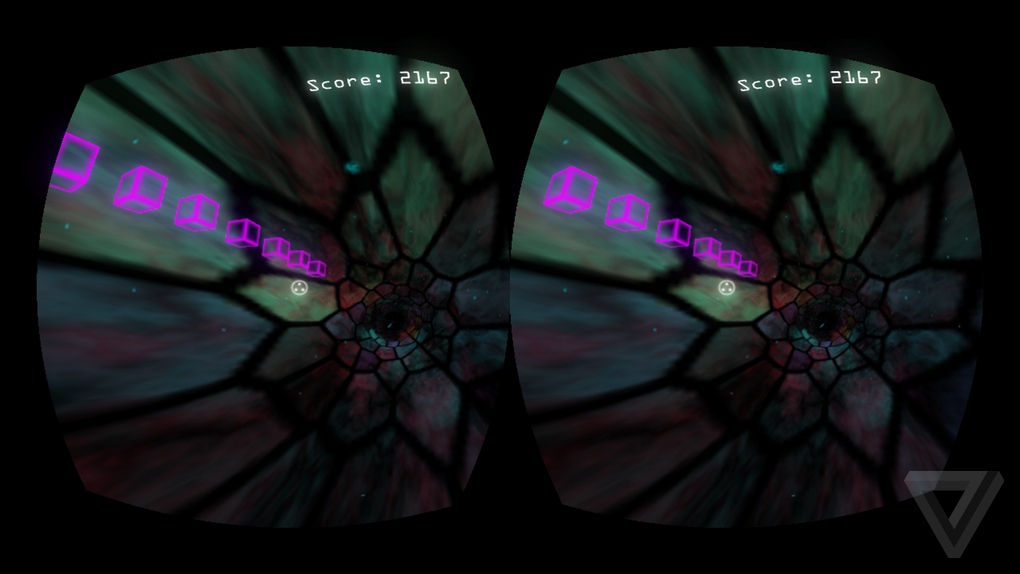

Once you break out of the first-person-shooter paradigm, dealing with VR’s limitations becomes less important than figuring out its strengths. Developer E. McNeill’s Ciess, which won the Indiecade VR Jam earlier this year, exploits what McNeill calls the "easy wins" of VR, eschewing realism in favor of abstract Neuromancer-esque cyberspace. "My pet theory is that we are very good at recognizing what realistic physics are supposed to feel like," he says. "Because that's never going to be perfectly reproduced with the first generation of the Oculus Rift, the solution is to kind of disjoint the player's mind from reality." In Ciess (pronounced see-ess), you’re shuttling around a web of neon data nodes, using your gaze to direct hacks and viruses.

"The less you are trying to manually override your camera controls and movement with inputs, the better off you are."

Although plenty of other Rift games are at least set in the physical world, breaking with strict realism is still often more comfortable than attempting to mimic it. At Owlchemy Labs, developers decided right away that a high-altitude base-jumping game was a perfect fit: players use the Rift’s head-tracking to look around them as they fall, with motion limited to shifting position laterally in the air. "With VR games, the less you are trying to manually override your camera controls and movement with inputs, the better off you are," says Reimer. The port (called Aaaaaculus!) is a long drop to a hard landing, but drifting around buildings to reach it is a surprisingly tranquil process, not least because no matter how fast you’re falling, your in-game body isn’t actually doing much.

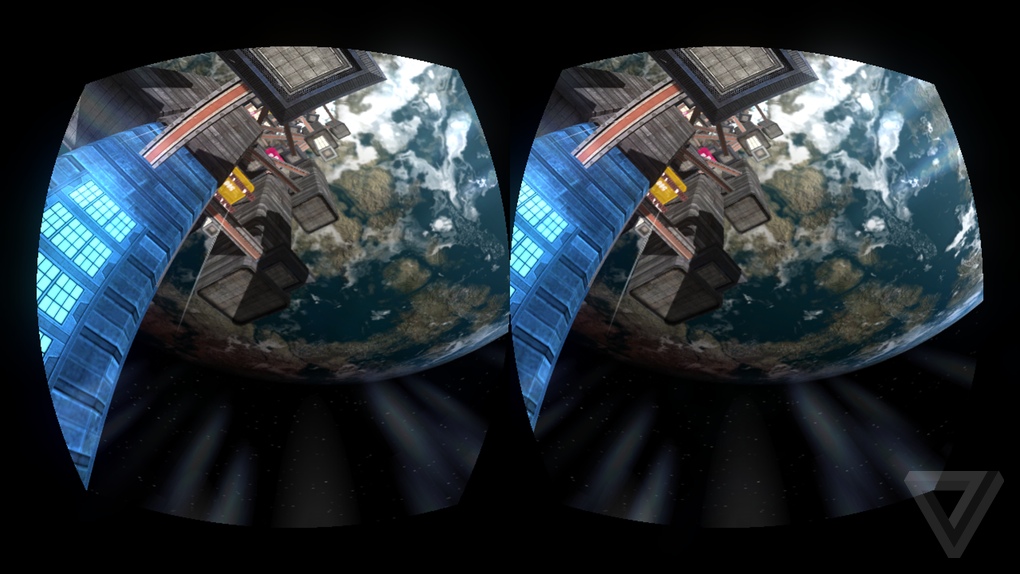

The most promising genres — and the ones that hew most closely to realistic motion — are those that involve driving or flying. Reimer calls race-car driving the "perfect one-to-one" link between reality and VR: "What you do in a real race car is: you sit in a spot and you look around. … And yet you're moving around the environment, because you're actually operating a motor vehicle like that." It’s not a purely aesthetic change, either: peripheral vision, he says, could let players keep an eye on other cars in a way that’s not possible on a monitor. If there’s a breakout Rift title so far, it’s spaceflight game EVE Valkyrie, which began as a tech demo from EVE Online developers CCP. The game pits you against other players in dogfights, letting you drift between asteroids while aiming missiles with your head. With a good community, it could be highly replayable, and despite the fact that you’re turning around in zero-g, the lack of any real environment stops your body from feeling too disoriented.

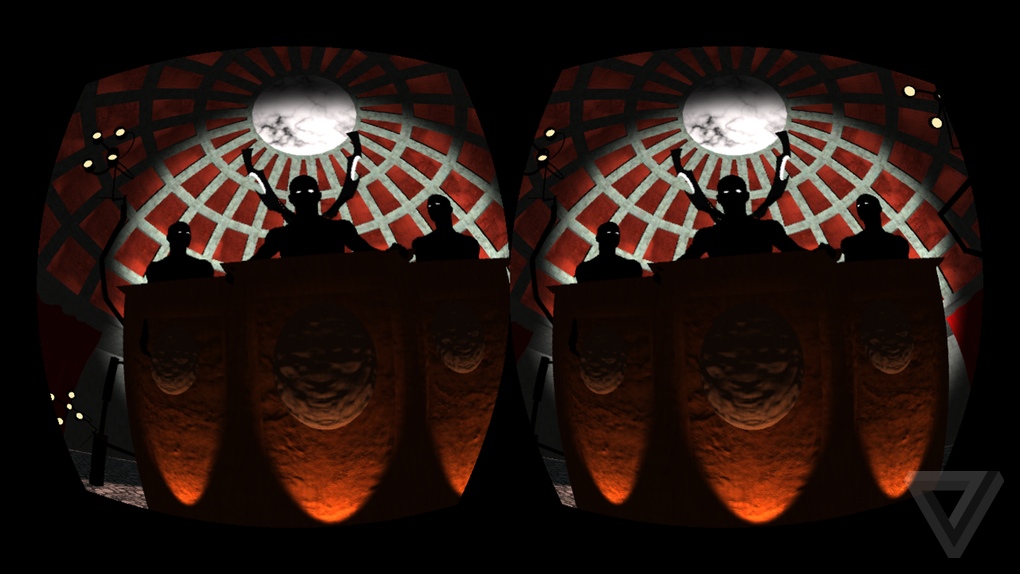

While most of the first-generation Rift’s properties make it unsuited for walking or running games, there’s an unsurprising outlier: horror. The Rift, by its very nature, is isolating. There’s nothing to distract you from the world of the game, and while it’s possible to play without headphones, you’ll miss out on directional sounds. All of which is augmented by the fact that in the Rift’s world, things can jump right into you. Remember the old, gimmicky days of 3D, when people would throw baseballs or bowls of popcorn at the screen? The Rift is the logical culmination of this concept, so much that non-horror developers end up having to work around it. "If something gets close to you, you will react as if something's going to hit you in the face," says Doug Wolanick, whose VR shooter Time Rifters is designed specifically to avoid these encounters.

Procedurally generated horror demo Dreadhalls takes full advantage of this instinct. Trapped in dark corridors, you’re not able to see more than a few feet in front of you, and you can’t see anything outside the game either. If something comes up to bite you, you know it’s not real, but you’ll still flinch because it’s right there, up against your face. If a statue moves, Weeping Angel-style, when you turn your back, you end up staring straight at it while you try to back out of the room, relying on your peripheral vision to navigate. Another horror title, Among the Sleep, exploits the Rift’s ability to make players feel out of scale with their environment: you play from the floor-hugging perspective of a two-year-old child.

The Rift’s immersiveness has also given rise to another, calmer experience: the virtual meditation or education chamber. One of Luckey’s favorite VR experiences is Titans of Space, which sends players on a virtual tour of the solar system. "It really makes a difference when you're at VR because you're rendering everything at the correct scale," he says. "It's not some abstract image on your screen, you're really feeling how large these things are, and that's something I don't think I've felt just playing on a monitor." Other demos, like "videodream" Iceland, can send you on tranquil trips across a landscape, gently floating rather than walking or flying. And the Rift’s all-encompassing design forces its wearer to pay close attention to environmental details, pulling them into a story or world. Non-gamers could one day look forward to a kind of personal IMAX or even, on the far more speculative end of the scale, a kind of Neal Stephenson Metaverse — Second Life, for one, has said that it will soon be adding VR support.

For the love of the Rift

Unfortunately, despite the "wow" factor of virtual reality, there’s still a limited amount to do on the Rift if you’re not a developer. Non-ported games tend to develop a single idea that can be explored in a short period of time: a Rear Window-influenced hidden object game, for instance, or a virtual trial that forces Rift wearers to respond to questions by nodding or shaking their heads. Wolanick is dedicated to turning Time Rifters into a full game, but he’s far from confident in the market at this point. He plans to release a non-VR version of Time Rifters, while staying involved with the developer and enthusiast community.

"It's not really about trying to build a base of customers as much as a base of ideas and developers."

"I think at this point, it's not really about trying to build a base of customers as much as a base of ideas and developers," he says. And to the outside world, he jokes, the Rift is still just weird. He recalls Frank Underwood’s predilection for PlayStation games on Netflix’s House of Cards: "You're like ‘Oh, wow, a dignified guy like that can sit back and play Call of Duty. That’s pretty awesome.’ And it looked natural. It didn't look unusual. But can you imagine him sitting down on his couch after a hard day and sticking a Rift on his face?"

Reimer, likewise, thinks it will take time to build a library of games that really take advantage of the Rift’s capabilities. "In the early days of VR, there are going to be a lot of games that would have existed without the VR component," he says. "That will kind of help with the drought, but it’s not building those amazing experiences. So there will end up being a library of games you can play with that, but not ones that were really specifically tailored to [the Rift]." Ideally, he says, there would be support for people who want to create VR-only games until a critical mass of users makes them economically feasible.

Ultimately, the success of Rift software will depend on its hardware. A new and improved Rift could turn today’s virtual reality, a fuzzy world seen through a screen door, into something that at least feels natural, if not necessarily realistic. An end to motion sickness would make it possible to play more genres of games for longer periods and make the Rift palatable to players and developers who aren’t already sold on the idea of VR. Until then, though, Luckey is counting on a dedicated community that sticks with the project out of love — even with no date for a consumer product. "A lot of people are so excited about VR that they aren't doing it because they have a product schedule ... a lot of them are doing it because they just really want to work on VR games."

"People were just foraging in a world where they didn't know what the heck they were doing."

So far, games and demos have managed to get pieces of the VR puzzle right, but their creators admit nobody’s quite sure what works yet. "VR kind of feels like when touch screens were brought to market, in the sense that developers were developing things blindly for it but there were no standards. And no one really knew the best way to deal with touch screens," says Reimer. "When you pick up an iPad or an Android device, it's understood that there's going to be pinch [to] zoom, and there's going to be finger drag and scaling and page-turning and tap and hold, and all those ideas are established and kind of understood as obvious. But at the time, people were just foraging in a world where they didn't know what the heck they were doing."

0

0

0

0