Five Generations: A Look at Oath

History is a funny thing. Ask yourself, what era do you live in? The modern age? Postmodern? Information? The Holocene, more specifically the Meghalayan? Or will the historians of far-flung generations assign a designation that doesn’t capture any of the details you personally associate with this moment? Everything our culture has accomplished, compressed by distance and necessity, into the Aluminum Age. At long last, the dead of the Bronze Age will nod in satisfaction at our diminishment.

When I spoke to Cole Wehrle about Oath, he called it a “hate letter” to civilization games and legacy games. It’s easy to see why. Like digging the fragments of a lost civilization from the compacted mass of an ancient trash heap, there are fragments to be found, shards and sherds, enough to make out an unmistakable imprint or two. Oath is a civilization game, but not like any you’ve played before. And it’s also a legacy game, but even less familiar. This is what I think about it. This is also the story of my first six plays. I hope you’ll soon understand why they’re the same thing.

The First Generation: Petty Lordlings

One of the challenges facing historians is the question of beginnings. Where do you start when describing a thing? In nearly every case, there is no clear-cut moment that delineates one age from the next, wartime from peace, ascent from collapse. Everything flows together, like ink in water. To a much smaller degree, the same is true of describing a board game, as long as you don’t chicken out and start with page one of the rulebook. Doubly so for good board games. When everything in a design carefully interlocks, which details are the most important?

Fortunately, Oath has a beginning, one carefully selected to draw players into the fold. There will be court intrigues and tenuous diplomatic inquiries and unexpected victories. Yes, yes, and much more. For now, though, that’s all hazy prophecy. Don’t worry about learning the cards. Don’t fret over how to manipulate the six clans. All you need to know is that there are eight sites on the map.

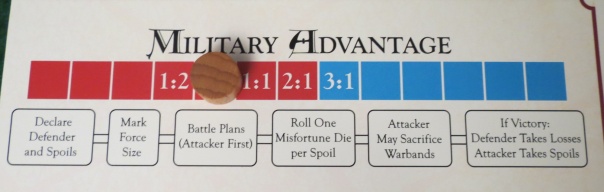

The goal of your first game is to control these sites. Oath’s system for resolving military actions may seem counterintuitive at first. You weigh your number of troops against your opponent’s number of troops. So far so good. You line up this ratio on a track. 3:1 provides great odds, already in the “victory zone,” provided you roll well and nobody pulls anything tricky. 2:1 and you’re already looking at casualties. 1:1 or 1:2? If those are your odds, maybe you shouldn’t even be fighting this battle.

Here’s where it gets peculiar and a little bit brilliant. Rather than targeting only one site, you can attack as many as you like owned by the same rival. This makes wild swings possible, but also presents a twofold challenge. First, you’re clashing with all the troops at all those sites at the same time, worsening your combat ratio. Second, you’ll need to roll a die for each site you’re targeting — and dice are bad. Possibly even very bad. Just to give you a sense for how crummy the dice can be, our first play resulted in one player frittering away the largest army in the game because of too many rolls that doubled his casualties. He won the campaign and conquered half the map. But his army was so weakened that his holdings didn’t last a single round.

Campaigning, like a lot of things in Oath, comes across as impenetrable for all of five minutes. Then its click-point arrives and everybody is calculating battle odds on the fly. It isn’t even the longest action, in terms of seconds spent resolving it. Meanwhile, that phrase — peculiar and a little bit brilliant — worms its way from the table into your brain. Get used to it. Nearly everything in Oath is peculiar and brilliant at the same time.

The Second Generation: The Goff Dynasty

Our first play ended with a mistake, as first plays of peculiar and brilliant games often do. This led to the formation of a dynasty under a new ruler. A shudder-worthy ruler. Geoff. Brrrr.

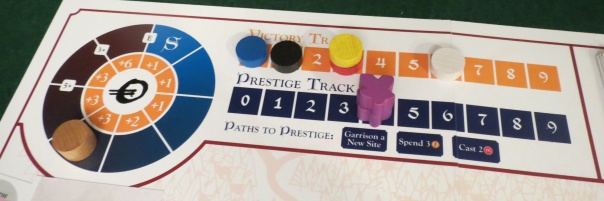

But to understand our mistake, you first need to understand how Oath is played. Every match is built around one of four victory conditions. For our first game — and likely for yours — the goal was to control the most sites. If at the end of their turn somebody held more sites than anybody else, they earned points. One point during the first few rounds, then two on the next, then three. These escalating points are something of a catch-up system, but one that’s earned. The more a struggle drags on, the more each victory means. Hence all those risky last-ditch campaigns to conquer a bunch of sites with a single action.

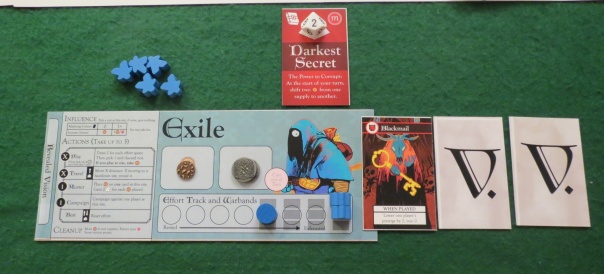

There are two significant wrinkles to this process. First, Oath is interested in the machinery of power; one of the ways it investigates this is by refusing to place everyone on equal footing. Most players begin the game as Exiles. Being untethered to the inner workings of state, Exiles are flexible. They’re the folk of the fringe, carving out fiefdoms and getting up to trouble as they see fit. Meanwhile, one player, customarily the victor of the previous game, is the Chancellor. This is the fellow in charge of the state — in our case, Geoff. In thematic terms, he was now playing as the descendant and inheritor of the dynasty he’d founded in our previous game. The thing about power, though, isn’t only that it corrupts. It also erodes. Despite the privileges of his rank, like extra armies and no small measure of intimidation, the Chancellor only gets two actions to each Exile’s three. To mitigate this, the Chancellor can invite Exiles into his realm, enfranchising them as Citizens.

There are advantages to shedding your cloak and becoming a Citizen. You’re done worrying about victory points and petty fiefdoms. All your armies are replaced by state soldiery and your goals are brought into severe focus as you endeavor to help the Chancellor’s faction win.

This isn’t to say you can’t win. In fact, depending on the way things shake out, your success might be easier than ever. Rather than jockeying for victory points, your marker shifts down to the prestige track, which you can advance along through primarily economic means. Now you’re competing against the Chancellor and any fellow Citizens to become the foremost figure in the state when it wins the game. In other words, while you continue the struggle externally — fighting battles, taxing and gifting resources to the Chancellor, amassing magic — you’re also wrestling for dominance within the grand halls of the empire itself. Cue plenty of grandstanding and the occasional conspiracy.

This alone is a wonderful inversion of power, but a familiar one. In fact, the closest analog is being a member of a coalition in Wehrle’s own Pax Pamir, except here there’s only one coalition, and you’re either inside or outside of it.

But here’s the thing: as an examination of how the powerful have struggled against each other across the centuries, it captures a particular dynamic almost perfectly. Power may be corrupting and eroding, but it’s also blinding. Picture Roman senators so caught up in their personal squabbles that they barely recognize the hordes amassing along the frontier. That blinding security is how it came to be that Chancellor Geoff invited two Exiles into his court, ran himself ragged on intrigues, and didn’t notice Somerset quietly seizing control of the dynasty, relocating the capital to a desolate ruin, and launching a popular revolution.

The Third Generation: Ruinous Republic

Oath is a legacy game. Sort of. You’ll never tear up a single card, sharpie an insulting name on the board, read endless paragraphs of somebody’s overwritten fan-fiction, or endure a preordained “twist” that has nothing to do with any of the actions you’ve undertaken during play. Instead, the conclusion of each game determines the setup of the next. I’ve already mentioned that the victor becomes the next match’s Chancellor. The deck also transforms, some portion of the unwanted discards being swapped out for cards matching the suit of the winner’s personal retinue. And the map changes, the victor’s holdings determining the landscape of the state made in their image, much like so-called Rome suddenly becoming centered around the onetime frontier towns of Metz and Aachen.

When Somerset launched her rebellion, all she controlled was a ruin. Hence the republic she founded was a crowded shantytown, rich in magic but poor in pretty much everything else, and brimming with discontented Exiles. It never stood a chance. To explain why not, we need to talk about visions.

The most complicated action in Oath is also the one that seems like it should be its most basic, the drawing and playing of a card. You pay some amount of effort — your main resource, easily refreshed with a rest action, but also easily spent — to draw a bunch of cards. From these cards, you select one and only one to play. That card can be played to the map, where it becomes part of the ever-shifting landscape, or to your cohort, a personal retinue of cards that only you can access. In effect, you’re building two tableaux: one shared and one of your own.

These cards are everything. Defenses. Battle plans. Taxable villages. Magic spells. Single-use booby traps. Ethnic groups which, when settled, bestow some of their favor. Mustering points, which gobble up that same favor in exchange for service in your armies. Free actions. Rule-breakers. Everything. They’re all conditionally useful, but because you can only choose one, drawing a handful at the same time tends to hit pause while you evaluate which to claim, and how, and whether to discard something precious with the intent to muck it back into your hand later.

And none of them are nearly as excruciating to see on the table as visions.

Visions are plainly marked on their back. The mere act of picking one up alters the cost of drawing from the main deck, so all the better to reduce the likelihood of error or cheating. More importantly, they’re marked because they’re threats. All cards can be stored face-down in your cohort, waiting for the moment you’ll reveal them to the world. Visions tend to remain like this, hogging up one of your three cohort slots, because they’re announcements. Harbingers of change. Bellowed challenges.

Alternate victory conditions.

The Fourth Generation: Secrets of Church, Secret Visionaries

Almost exactly like the alternate victory conditions in Wehrle’s Root, actually, although they’re easier to accomplish. If your turn rolls around and you’ve met the proper conditions, you win regardless of where everyone stands on victory points. There are a few subtleties beyond that. For one, there are only four visions that offer new objectives. If an Exile grabs a vision and then immediately claims the Royal Blessing, one of two special cards that changes hands often, there’s a good chance she’s chasing a win. Even Citizens, who are too close to the Chancellor to accomplish a vision unless they first renounce their allegiance and return to Exile status can hold the things face-down, like lingering blackmail notes, provided they’re willing to clog up a portion of their cohort. Visions can even be buried in discard piles and dug up again. Just be careful nobody comes along and ushers in a new dynasty while you’re preoccupied elsewhere.

Oh, and that mistake we made on our first play, the same mistake that’s been repeated almost every time a new player has dropped into our ongoing history, is that a vision needs to be face-up before you can accomplish it. There’s no gotcha! to a vision. Everyone gets a chance to disrupt your plans. Which means you need to be exceedingly careful about when you finally reveal one.

Turns out Geoff didn’t win. All is right with the world once more. The realization almost soothed the sting of Jessica deploying a hidden vision to form a repressive theocracy.

The Fifth Generation: Republic Reborn

There are other details to consider — those aforementioned special cards that pass between players whenever they’re purchased, the intricacies of how and when the Chancellor and Citizens can trade resources, even the way those resources represent each clan’s favor and might witness them growing stronger or waning into obscurity across multiple plays. At times these details are crystal clear; other times they’re slightly muddied. Unlike most prototypes, Oath has been polished until its best and worst parts are readily apparent. The good news is that, unlike both Root and Pax Pamir, even as a prototype Oath comes across as a complete game. Despite my copy arriving on taped-together cardboard, with placeholder illustrations and the odd cube in place of a meeple and mismatched colors, it acquitted itself as finished. Or near enough that plenty of finished games never arrive at a more complete state.

The thing about those details is that none of them matter alongside the story we crafted over multiple plays. Five generations, I told myself; five will be enough to observe the game’s mythos in transition. Yet as soon as our fifth play was wrapped, we played again, and then again. Oath had become a minor obsession. Everyone needed to see where it would lead. We weren’t following a prewritten narrative, two thousand numbered paragraphs in a spiral-bound playbook. We were following our narrative. The story we wrote across centuries.

After a military catastrophe unmade the invincible armies of the local bully, our culture’s exhausted warlords were brought to heel by a dynasty. A broken dynasty based on lies and mistakes, but such a thing wouldn’t be the strangest occurrence in history. Generations later the dynasty had grown fat with the plumpness of assumed rule, and imploded into a ruin of its former self, literally inhabiting the ash-blown husk of a demolished city. At least we had a representative government. Which we endowed with a voice by dividing into bitter factions, refusing to cut a deal with anybody, and squabbling over scraps until hardly anything remained. From that time of strife the church arose, broader and stronger, its laws delivered via esoteric mysteries and closely-guarded secrets. When we reestablished the republic — only after another dynasty’s interregnum, after another savage period of warlords cutting a path across the steppes — there was no reason to declare it the end of history. But it seemed right. I sorted the cards back into their original piles. Gone were the radical new powers we’d folded into our plays. Gone were the clans and their respective pecking orders. All that remained was the history.

I’ve played hundreds of games about history. Oath may be the first game I’ve played about historiography. Just as Rome was a kingdom before it was a republic, and then an empire before it became an instrument of religion, the culture we raised could be traced from root to branch, the sum total of many small decisions. Military campaigns, a blade in the dark, shrewd merchants, frontier explorers, collusions, divisions, the choice of one companion over another — all mattered as often as they were lost to time.

Moreover, Oath answers the questions left hanging by other civilization games. Who are you? Where are the internal challenges to your power? Rather than shepherding a culture from BC to Far Future CE, each play resembles a single pivotal turn in a larger epic. These are the watersheds, the revolutions, the moments when power was seized and crises were faced and buried. And when we played, our history was written by our own hands. Wehrle might call it a hate letter to civilization games and legacy games. But that’s only half the story. Oath is also a love letter.

And through it, I can’t wait to experience another chance at writing some history.

Oath will be on Kickstarter on January 14th. You can find it here.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A prototype copy was provided.

Posted on January 8, 2020, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Cole Wehrle, Leder Games, Oath. Bookmark the permalink. 47 Comments.

Very interested to see this game. I tend to love the the idea of Coles games more than playing them and I hope this one bucks my personal trend because the idea is fantastic.

For what it’s worth, it’s more approachable than some of his games. Probably less approachable than Root. Maybe tied with Pax Pamir 2. Hard to say. I’ve played so much that I dream in Oath now.

But I found Pamir 2 much more approachable than Root!

Heh. But Root features gentle woodland creatures!

Fantastic read, Dan. We all can’t wait for this one, I am sure.

Thanks, Alexandre!

My goodness Dan. You’ve somehow gotten me even more excited about this.

The only wrinkle that concerns me. If someone wins and earns the right to be chancellor, but they can’t make the next game, is it still playable?

Yeah, it doesn’t matter all that much. More than any “real” legacy game, it doesn’t fall apart if somebody misses a session. Stringing plays together is a big part of the draw, though, so definitely shoot for having the same folks bounce in and out if possible.

Wehrle, you magnificent bastard.

He tops his last trick of slipping a COIN game past the normals in a cutesy animal skin by putting a CRT into this one! I expect the next Wehrle to feature Smurfs exerting zones of control. 🙂

At this point, I wouldn’t be surprised if Wehrle sneaks a dense hex-and-counter game into a woodland war-euro that sells out in two minutes. ASL: Advanced Silva Leder.

This is why I read Space-Biff! Dan, this is a wonderful write-up, and I couldn’t be more excited.

Everybody else? READ THE ALT TEXTS.

Thanks, Matt! You’re too kind.

Another great write up about another game lots of peeps probably won’t be familiar with (myself included). Brilliant writing. Great stuff. I hate you. Lol

Ha! Thank you for the hatred!

You are going to make me do something I’ve said I’ll not do.

Get into a kickstarter 😛

Well I can think I can make 1 exception per year or so.

Jesús! No! Be strong!

Although if you MUST pick one…

This is my rule as well and I’ve kept to it up until now. This year I’ll get my 1 in January it looks like. I may also get another 1 if John Company gets to kickstarter. Maybe another 1 if Sidereal Confluence gets to kickstarter. Maybe another 1 for Viscounts of the West Kingdom.

Only 1. I only pay for 1 at a time.

Thanks for this,Dan

And thank you for reading!

Awesome write up (again!).

I’ve been enjoying reading Cole’s designer diaries but this multi-session write up really captures the storytelling feel I was hoping to see come out of the gameplay.

Roughly what gametime was covered over these plays?

We played about ten times. Most of our plays were in the 75-100 minute range, although with five players it got as high as 120 minutes.

I’m curious, how many players did you usually have? How well do you think the game would work with only three players?

I tried it at all counts supported by the rules I was sent. Most of our plays were at 3p or 4p, both of which worked very well. 2p was functional, but a little thin — however, we didn’t have access to the AI Chancellor that will apparently be featured in the finished game. 5p was still enjoyable, but as you might expect there was more downtime between turns and it ran a little longer than I usually prefer.

I wonder (as usual) how it might work only for 2 players…

When we played 2p, the game functioned but felt a little too thin for my liking. However, we didn’t have access to the AI Chancellor that will be in the finished game. So I have no insight on how well that’ll work.

Great review of a game that looks very appealing to me. Thanks!

Thanks for reading!

Great write-up Dan! I was very surprised to hear of the Jan launch date given that it sounded as of early December like it was still going through pretty major design-level changes. This sort of seems to be a thing with Leder, that they launch before the game is actually finished. With Root this resulted in a need for later patches, which, ok, it happens. But it sounds like Oath is much more complex and the card deck much larger, so I would have expected a pretty extensive development cycle would have been needed. How “done” did the game feel to you? Are there still a lot of rough edges?

Leder games seems to be one of the few board game companies that treats Kickstarter at least a little like a traditional venture capital platform instead of just a straight pre-order system. Well…maybe they fall somewhere in between those extremes. Point is, you’re funding more than the material and shipping cost of an existing product, you are also very transparently paying for the development of that product. The risk of venture capital is always that your investment doesn’t result in a product/business as good as the initial vision.

But in defense of Leder, Cole, and Root, it’s at least worth noting that the changes to Root are in the interest of “balance”, and are thus somewhat opposed to the initial vision/concept of the game. It is not as if the changes are necessary to make the game playable. They are simply introducing balance to a game that I suspect is more interesting without it.

I am confident that Oath will be a similarly excellent game, and I am equally skeptical that it will be well-served by balance.

Good question. I’m obviously not privy to the inner workings over at Leder, but this is by far the most feature-complete prototype I’ve received from either them or Cole Wehrle. Vast 2, Pax Pamir 2, and Root all had their good points in prototype form, but apart from the homebrew components this one feels like it could have come home with me from a store.

As for complexity, this isn’t anywhere near as complex as Root, at least balance- or teaching-wise. It probably helps that Wehrle is more assured as a designer and the Leder team is getting stronger at development.

Hi Dan, excellent writeup as usual! How did you like the matches played under one of the two privileges or popular support compared to vanilla (supremacy) oaths? I try to imagine what it would be like to play under the three alternative oaths, not the starting one. Which one did you like best? Thanks again.

What I like about the oaths is that they generate very different approaches despite all being fairly easy to “read.” Conquest obviously starts a lot of wars. The privileges tend to be economic, with loads of theft between players. Popular Support is the hardest to parse on a turn-by-turn basis, but it’s not that bad, and leads to a lot of careful jockeying for which suits you pay into or draw out of. As for favorite… probably Popular Support due to a recent play, but I’ve enjoyed them all.

Interesting. This might be the real litmus test of the game. I mean it’s one thing to wage wars all the time due to the Oath of Supremacy (it’s quite straightforward, we do that all the time in every second game). But to win on Dynasty, Rebellion or Faith could be something else; can’t wait to play by those oaths with a slightly modified world with the same people. Fun times ahead.

What are your thoughts about how this should be played in terms of the players?

I mean, do you think it would be better to approach it as “legacy” (even if it isnt) for the shared history, or that it is reasonably and not a big deal to have the evolving history basically being whoever was there to play and wanted to? Will it then be reflected somehow, or people would just see the last state of play?

Would it also be difficult to have, say, several concurrent “campaigns” going on? Or it would be just a question of taking some small notes about what was the last state of play with group A,B,C…

I’ll answer the campaign question first. In essence, it’s possible to save multiple game states, but officially you’re only supposed to save one. You’d have to take a lot of pictures and notes to save more than one state.

As for being a legacy game, it’s easy to drop people in and out. It isn’t necessary to stick to the exact same group. That said, it’s a good idea to stick to MOSTLY the same group. You don’t need to pause if somebody can’t show up to a session, but much of the fun is found in seeing how the long-form narrative develops. That works best with a regular crowd, even if they need to rotate in and out.

Hey Dan,

great Review! I have Pax Pam 2nd Ed and all things considered, it and Oath seem fairly similar, loyalty-switching, card-based Area control etc. Do you think it’s worth it having both?

Depends! Pax Pamir 2e is the better game for a single session. One of my reservations with Oath has more to do with the tone of today’s hobby landscape than with the game itself; namely, when people treat their games as disposable experiences, will it find groups willing to play it a handful of times to see what it has to offer? If it does, it’s an incredible experience. Otherwise, it’s “merely” a very good game.

Damn, quite the write up. As a fan of the political challenge games, I know that my gaming group needs a considerable amount of investment to get something epic like Twilight Imperium 4 going – sounds like this is in a similar vein with a shared story between much more digestible sessions.

I think Leder has you to thank for swinging me into backing something for my first ever Kickstarter backing!

Heh, thanks for reading!

My immediate reaction to this excellent write-up was “Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough”, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. in Buck v. Bell, a 1927 Supreme court case upholding a Virginia law that authorized the state to surgically sterilize “mental defectives” without their consent.

Any resemblance to persons living or deceased is entirely coincidental.

Dan, how did you play this in your group: Are there a lot of deals made at the table, negotiations and diplomacy? I always found those to be a bit complicated in boardgaming. I played “Diplomacy” by email…

Depends on the play. Some discussion, some ganging up. But for the most part, not too much negotiation.

Pingback: On Seeking that Elusive “Cardboard Flesh.” | Cardboard Arcana

Pingback: Spiel 2020 – Daily Delusions

Pingback: Oaf | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: 5 on Friday 23/02/24 – No Rerolls